Kelly Lectureship traces advances in pigmentary diseases

Reliable treatment inching closer to market.

N001 – A. Paul Kelly MD Memorial Award and Lectureship

Saturday, July 23 | 9-10 a.m.

The future has never been brighter for patients with pigmentary diseases. The FDA recently approved the first JAK inhibitor for vitiligo, transforming an off-label approach to standard of care. Similarly, new findings in melasma are bringing reliable, efficacious treatment ever closer.

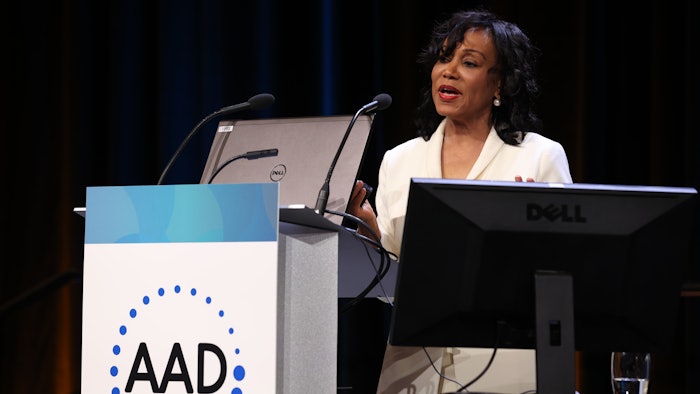

“Both of these disorders, despite being at opposite ends of the spectrum, involve a unique cell, the melanocyte, and they both impact quality of life,” said Pearl E. Grimes, MD, FAAD, director of the Vitiligo and Pigmentation Institute of Southern California and clinical professor of dermatology at the University of California in Los Angeles. “That unique cell is responsible for giving the skin its color, photoprotection, barrier function, camouflage. And it is the only cell in the body that gets involved in politics and causes division. We love it or we hate it, we want more of it or less of it, and sometimes both at the same time.”

Dr. Grimes described her ongoing relationship with melanocytes during the inaugural A. Paul Kelly, MD Memorial Lectureship N001 – Challenges, Conundrums and Innovations: The Changing Landscape of Pigmentary Diseases on Saturday. She worked with Dr. Kelly for 12 years.

“He was my esteemed colleague, research collaborator, brother, and mentor. Dr. Kelly will always hold a special place in my life and in my career,” Dr. Grimes said.

The promise of JAK

For many clinicians, vitiligo has gone from an untreatable depigmentation to a treatable condition, thanks to the development of Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors and ongoing research that has characterized key pathways leading to induction of melanocyte destruction and depigmentation. Genetic susceptibility, oxidative stress, and other factors trigger a CD8+ T cell-driven destruction of melanocytes. Recruitment of the CD8 + T is regulated by interferon gamma activation of JAK-signaling that induces the expression of multiple inflammatory mediators that damage melanocytes.

“We have made history with the first FDA-approved drug for repigmentation in vitiligo, ruxolitinib,” Dr. Grimes said. “Those of us who have been involved in these studies are delighted that this is coming to change the landscape of vitiligo. Not only will we have an approved treatment, emerging data gleaned from the Phase II JAK inhibitor trials may allow us to delineate responders versus non-responders in vitiligo.”

Although the efficacy of JAK inhibition in clinical trials is similar regardless of skin type or duration of disease, younger patients generally responded better than older patients. Other differences between responders and nonresponders showed that vitiligo patients who had a facial VASI (vitiligo area scoring index) of 50 or better at six months skewed toward a Th2-mediated inflammation whereas non-responders skewed toward Th1/ Th17.

More data on pathways needed

“One of our greatest areas of need is new data on pathways to expedite repigmentation,” Dr. Grimes said. “How do we get out of the gate faster and speed up the process? And how do we maintain repigmentation? New studies are currently addressing memory T cells that play a major role in reactivation of vitiligo. The future is to continue to fill in those gaps in knowledge.”

Pathogenesis of melasma completely different, newer treatments needed

Recent studies suggest that it represents a phenotype of photodamage. While melasma has long been associated with sun exposure, Dr. Grimes said, new data point to photodamage from visible wavelengths as well as ultraviolet. The complex pathways driving hyperpigmentation in melasma extend beyond melanocytes to keratinocytes, mast cells, fibroblasts, sebocytes, and other cells. Blood vessels also play a role.

“We are looking at better treatments for photoprotection,” she said, “including the importance of tinted sunscreens containing iron oxide for visible light protection. And even though we still use hydroquinone, we continue to look for that non-hydroquinone Grail.”

Her lab is working with a novel lightener, malassezin, derived from Malassezia furfur, a fungus resident in the skin microbiome.

There is also evidence that mast cell mediators stimulate the angiogenesis seen in melasma. Oral and topical tranexamic acid has come into global use, but there is enormous need for newer agents that are more effective with fewer adverse events.

“There are so many gaps with melasma, so many pathways that are involved,” Dr. Grimes said. “A key need is newer and better treatments that are durable. We must prevent the relapse of melasma, which is so frustrating for patients.”

Visit AAD DermWorld Meeting News Central for more articles.