Insects, spiders, and ticks, oh my!

What’s bugging a patient might be an actual bug.

Dissecting the dermatologic significance of exposure to arthropods was the focus of “F060 – What’s Bugging You? Arthropods of Dermatologic Importance and Their Management: An Up-to-Date Review,” directed by Eric Hossler, MD, FAAD, a Geisinger Health Systems dermatologist and dermatopathologist. Bethany Rohr, MD, FAAD, joined Dr. Hossler to answer key, clinical questions about the varied cutaneous reactions to arthropods and provided practical management tips.

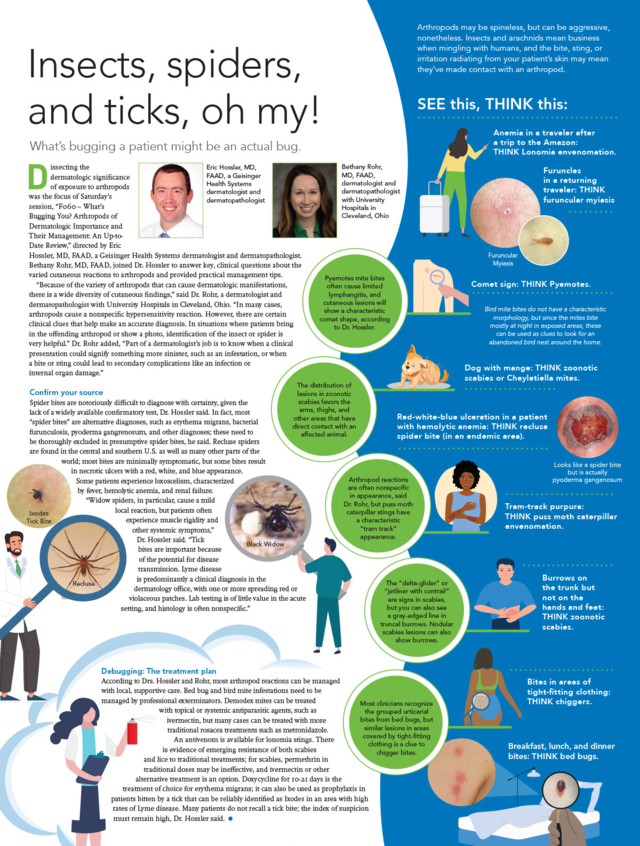

“Because of the variety of arthropods that can cause dermatologic manifestations, there is a wide diversity of cutaneous findings,” said Dr. Rohr, a dermatologist and dermatopathologist with University Hospitals in Cleveland, Ohio. “In many cases, arthropods cause a nonspecific hypersensitivity reaction. However, there are certain clinical clues that help make an accurate diagnosis. In situations where patients bring in the offending arthropod or show a photo, identification of the insect or spider is very helpful.” Dr. Rohr added, “Part of a dermatologist’s job is to know when a clinical presentation could signify something more sinister, such as an infestation, or when a bite or sting could lead to secondary complications like an infection or internal organ damage.”

Confirm your source

Spider bites are notoriously difficult to diagnose with certainty, given the lack of a widely available confirmatory test, Dr. Hossler said. In fact, most “spider bites” are alternative diagnoses, such as erythema migrans, bacterial furunculosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, and other diagnoses; these need to be thoroughly excluded in presumptive spider bites, he said. Recluse spiders are found in the central and southern U.S. as well as many other parts of the world; most bites are minimally symptomatic, but some bites result in necrotic ulcers with a red, white, and blue appearance. Some patients experience loxoscelism, characterized by fever, hemolytic anemia, and renal failure.

“Widow spiders, in particular, cause a mild local reaction, but patients often experience muscle rigidity and other systemic symptoms,” Dr. Hossler said. “Tick bites are important because of the potential for disease transmission. Lyme disease is predominantly a clinical diagnosis in the dermatology office, with one or more spreading red or violaceous patches. Lab testing is of little value in the acute setting, and histology is often nonspecific.”

Debugging: The treatment plan

According to Drs. Hossler and Rohr, most arthropod reactions can be managed with local, supportive care. Bed bug and bird mite infestations need to be managed by professional exterminators. Demodex mites can be treated with topical or systemic antiparasitic agents, such as ivermectin, but many cases can be treated with more traditional rosacea treatments such as metronidazole.

An antivenom is available for lonomia stings. There is evidence of emerging resistance of both scabies and lice to traditional treatments; for scabies, permethrin in traditional doses may be ineffective, and ivermectin or other alternative treatment is an option. Doxycycline for 10-21 days is the treatment of choice for erythema migrans; it can also be used as prophylaxis in patients bitten by a tick that can be reliably identified as Ixodes in an area with high rates of Lyme disease. Many patients do not recall a tick bite; the index of suspicion must remain high, Dr. Hossler said.

Visit AAD DermWorld Meeting News Central for more articles.

Click to view or download infographic from the print daily