What’s causing those pediatric allergies?

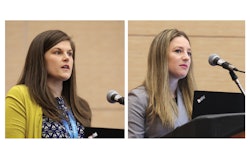

Speakers review current food allergy guidelines for infants with atopic dermatitis.

A pediatric allergist and pediatric dermatologist teamed up for Saturday’s U031 – Preventing Food Allergy in Pediatric Atopic Dermatitis: Applying the New Guidelines to Your Practice. The duo provided background and case studies on food allergy in atopic dermatitis, providing references to relevant guidelines. Although they primarily focused their remarks on peanut, they also referred to milk/egg, soy, wheat, tree nut, shellfish, fish, and sesame.

“As a pediatric dermatologist, the most gratifying thing I do is to help a child overcome atopic dermatitis, which improves their quality of life,” said Lacey Kruse, MD, FAAD, attending physician at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago and assistant professor of pediatrics and dermatology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. However, applying current guidelines can be challenging, especially with the many variables of food and environmental exposures that can serve as the trigger.

Current food allergy guidelines recommend that infants with atopic dermatitis be introduced to peanut-containing foods between four to six months of age to prevent peanut allergy.

“Children should be eating food that they can tolerate,” Dr. Kruse said. “Food avoidance could encourage a true allergy.”

To introduce peanut to an infant, Dr. Kruse recommended adding peanut butter/powder to breast milk or formula, starting with a small amount, and monitoring the infant for 30 minutes. If there is no reaction, she suggested feeding at least two teaspoons. If tolerating, continue to feed two teaspoons of peanut butter daily.

Infants with severe eczema, egg allergy, or both should have a direct referral to allergy test or serum IgE screen; if negative, feed. If positive, refer to allergy test, and if IgE is negative, introduce peanut at four to six months.

Anna Fishbein, MD, attending physician and associate professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, defined a food allergy as an adverse health effect arising from a specific immune response that occurs reproducibly on exposure to a given food. “The key is reproducibly,” she said. Lactose intolerance, food protein-induced proctocolitis, behavioral changes with foods, fever, or mild diarrhea are not food allergies.

Not all allergens are the same, she said. For example, baked milk or egg can help an infant outgrow an egg allergy, roasting peanuts makes them more allergenic, and fish and shellfish are most easily aerosolized, which makes reactions around cooking common.

Dr. Fishbein provided her pearls on food-triggered eczema. “Consider practical thinking,” she said. “If there is no peanut in the diet or the home, it is not triggering eczema.

“It can be confusing because even IgE-mediated reactions cause eczema flare. We see this after food challenges all the time,” she said. She also noted that food patch testing is not predictive.

As takeaway items, Dr. Kruse recommended introducing peanut into patients with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis at four to six months of age, have an allergist on tap to help with challenging patients — especially those with severe atopic dermatitis — and decide if you are comfortable introducing testing versus referring infants with severe atopic dermatitis.